As I look back on my formative years I recall a few outstanding moments and events that inspired me and provided me with insights and direction. They have relevance to this book because they reflect my struggle to understand the enormity of information, to master the skills necessary to apply the knowledge. My hope is that the reader may be directed and even inspired by these stories.

The challenge of failure

On the first day of medical school I was sitting in the back of Chemistry class in Johannesburg, South Africa when Professor Sam Israelstam cocked his head cynically and asked us as the to look to our right and to our left. ?Only one of the three of you is going to make it through medical school,? he warned. The next lecture I zoomed to my new seat right in front of the class. There was no way I was going to be the one who did not make it!

That was 1970 and the world was different. TV had not yet reached South Africa, there were no personal computers, and there was no Internet. South Africa was culturally and intellectually isolated and relatively unsophisticated. Although I tried my best to keep up with the brightest (gauged by their superior grades), I realized that my memory for the number of double bonds in the complex organic molecules would not hold. But the fear of failing pushed me to memorize and rememorize innumerable facts to pass the exams, so that I could avoid the shame of failure. It would take me longer ? but I was not going to fail.

The key to controlling information

In my second year, Professor Hedrick Koornhoff taught microbiology- the study of germs. Again you would have found me in the front of the lecture hall painfully trying to write down each word and detail describing the many hundreds of bugs in the world. I could never write as fast as the professor could talk, and I found that by the end of the lecture I owned a scratch of words on the paper with no better understanding of the world of bugs ? and an ever looming fear of being the one who was not going to make it.

As I tried to reorganize the notes late one night I recognized a pattern in the lectures. The bugs were all described by a recurring pattern of adjectives. Size, shape, character of the culture medium they were able to grow on, and their staining characteristics were repeated themes. I realized that if I could create a template on the notepad before the lecture, I would be able to fill in the gaps as the lecture progressed. With this technique I was not at the whim of the next word uttered (and sometimes muttered) from the professor?s mouth, but was able to take take control of the lecture. The result? The information started to take on meaning for me once it was given context. There was thought involved as I listened. My needs had changed from wanting to own the information to wanting to understand, become knowledgeable and enjoy the information.

This had to be the answer! Thinking before I was writing, and understanding for the sake of learning, felt correct and satisfying. Acquisition of information without the benefit of becoming more knowledgeable felt wrong. This new power arose by allowing knowledge to stem from common principles, with detail subsequently positioned in a context and a framework. It was a truly liberating and memorable moment. Data, information and knowledge became stratified and clarified as distinct entities. Data were necessary yet unconnected and meaningless in isolation; information had some connections and some value, while knowledge was organized around a framework, and led the pack in value.

Understanding was yet another level. The human experience of comprehending something new or understanding something that never quite made sense is the ultimate reward in the industry of learning and knowledge. When the penny drops with new insight, we suddenly feel enriched. Our youngest daughter literally laughs out loud when she realizes that she has learned something new. While adults may not have the same giddy response, a quiet sense of satisfying acknowledgment is universal.

The control over my education reminded me of one of the opening passages of the Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck. Tom Joad had just been released from jail when he happened upon his old friend Muley Graves, a vagrant on the run who harbored resentment against the corporate businesses that had run him and his family off their farm.

?What?s come over you Muley? You wasn?t never no run-an-hide fella. You was mean.?

?Yeah!? he said, ?I was mean like a wolf. Now I am mean like a weasel. When you?re huntin? somepin you?re a hunter. But when you get hunted ? that?s different. Somepin? happens to you. You ain?t strong: maybe you?re fierce.?

The difference between the two states is an important psychological one. As the hunter, one is empowered; as the hunted, one is subordinate and powerless. In life, the two states are often exchange. Sometimes a little trick is taught, such as looking at the big picture first, and then filling in and applying the detail, which makes the difference between being the hunter and the hunted. It was for me at that time.

The beauty of form and function

Another formative experience came in my second year during Introductory Anatomy with Professor Philip Tobias. We were obliged to take the Hippocratic Oath before being allowed into the dissection halls. This introduction to anatomy was, therefore, one of our first entries as privileged people into the worlds and bodies of others, teaching us to maintain respectfulness and humility. Professor Tobias explained that we were going to spend a very intense year among the odors of formalin, delving into the secret innards of dead people, and that the body we?d examine was a mere remnant of the former person. The muscles and nerves would be exposed, the organs removed, and the face, the former mark and feature of a unique individual, would lose its identity.

| The Physician ? Understanding How Structure Function Disease Diagnosis and Treatment Fit Together |

|

Jacopo Berengario da Carpi (ca.1460-ca.1530) [anatomist] Berengario, an Italian surgeon and physician, refashioned the 14th-century anatomical treatise of Mondino de?Liuzzi for print publication. The illustrations give little anatomical detail, but visually represent the sense of wonder that attends the opening of the body. (National Library of Medicine ? need permission) |

In order to instill a perspective of the eventual purpose to this seemingly destructive method of learning, Dr. Tobias invited a duet of professional classical ballet dancers and a pair of black belt karate experts into the lecture room. He wanted them to display the beauty and form that pieces of muscle, nerve and gut can actually reach in their prime of health, when structure and function are in perfect harmony. To this he added the spark of a creative soul that drove these four people to their expressive peaks.

This experience inspired me to realize that biology, anatomy, medicine, health, disease, are all integrated parts of life. Learning one was not possible in isolation. In fact, nothing and nobody exists in isolation.

Albert Einstein or (not Albert Einstein)

In South Africa, I had to make the choice to study medicine while I was still in high school. We enter University and Medical School straight after graduating high school, without the advantage of a liberal arts education. After studying and interning in South Africa, I spent another seven and a half years delving into the detailed worlds of cardiology, pediatric cardiology, pediatric cardiac pathology, radiology and interventional radiology. My medical knowledge base was broad and somewhat deep, but my knowledge of other valuable cultural disciplines was rather shallow.

Against the advice of my medical colleagues, I donned a backpack and set off for a year exploring the world and also myself as a person. I looked toward cultural idols for inspiration, and one of these was Albert Einstein. Two small components of his thought process inspired me at the time. The first: he was purported to have lamented that we only use 10% of our mind?s capacity toward useful and productive thought, while 90% of the time our minds are in some twilight zone, thinking about our next meal or what to wear on our date tonight. His second axiom was of deeper relevance to me: the advice to place yourself in the position of the molecules or particles you are studying, and imagine yourself participating in the experimental event at hand. I started to imagine myself as a liver cell, lung cell, or brain cell, and became profoundly aware of the remarkable individuality of the cells of my body. I imagined myself as a lung cell coming into contact with a whiff of smog from the air, subject to the whim of a master being.

As a master being, an overall person, I became aware of the importance of team effort among my cells; they had to combine, cooperate and connect to bring each organ into productivity. Next, organs connected to form systems, and systems formed the functional and productive whole body. My privileged existence depended upon vital collaboration among cells, organs and systems. This experience evolved into an exploration of units and how they combine with other units to form something bigger and more powerful than themselves. The concept of Units to Unity subsequently became the essence of a philosophy that helped frame biology and disease in the larger community.

Untitled Document

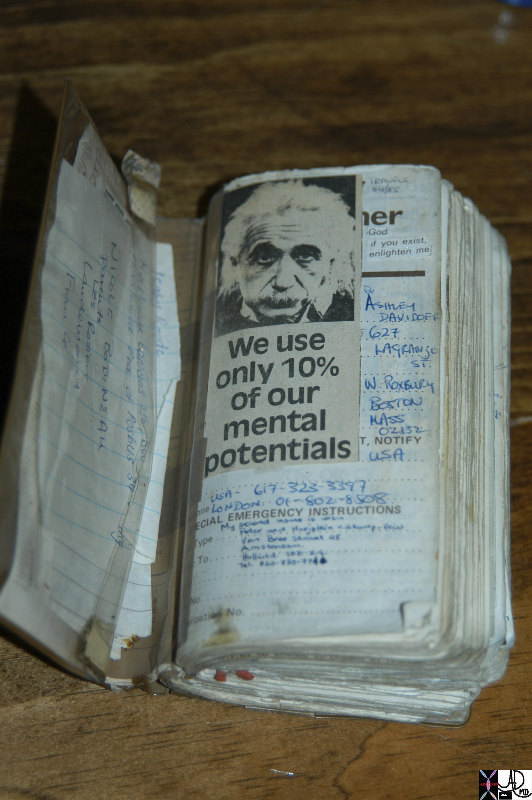

Tattered 1984 Diary ? Einstein my Hero |

|

|

Tattered diary from travels of 1984 with a picture of Einstein displayed prominently on the first page. Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD 86104p |

While I traveled I carried a little picture of Einstein in the front of my diary, reminding me each day that I should remember and apply these two concepts. The comical end and embarrassing irony to the story is that in my attempt to verify them, I have found no attribution for either of these wise and wonderful axioms to Einstein. Either way, the words and thoughts inspired me to higher levels that I have applied since that time.

Technical Skills

Pursuit of Excellence

When I was in nursery school at the age of three in Linksfield, Johannesburg South Africa, I began to dance whenever music was playing. An astute teacher relayed this inclination to my mother, landing me in Miss Lee Rom?s tap school at the age of four (much to my objections) and in dance competition at five. By the age of nine, I was also enrolled in Madame Gitanella?s school of flamenco dance (poor guy!). Every six months, from the age of five until 14, I was entered into regional and national dance competitions.

The preparation was intense, requiring three days per week training at the dance school and hours a week practicing at home. In order to maintain my ?manly? profile I participated in sports including soccer, swimming, tennis, cricket and rugby.

Three months prior to dance competition my mother would roll the carpet up in our living room and we would ?practice, practice, practice? until the dance was perfect. On stage I gave it all I had and allowed my ?inner creative self to be expressed,? at the advice and coaching of a loving parent. I learned to do pursue excellence, partly led by my desire for coveted prizes.

So many life lessons were learned from this experience which continue to ring true in my personal life and my professional life. It is so important to pursue of excellence in a chosen endeavor, to follow principles, and to master techniques.

If medicine is your chosen career it is imperative that you start out with a deep felt need to pursue excellence in all its facets.

Pursuit of Excellence in Medicine

Once the clinical rotations started in our fourth year of medical school, we were anxious and intimidated by the prospect of interviewing and examining real patients. The intimidation arose mostly from a need to remember the questions necessary to obtain a complete medical history, and to find a method to complete the physical examination without floundering embarrassingly in front of the patient.

The complete history and physical had to be flawless, since failing to ask one relevant question or examine for one relevant physical sign could conceivably result in a fatal error.

I was challenged to such an extent by this concept that my fear resulted in reticence. I lacked the confidence required to get on with it, examined and spoke to few patients and could not find a way to practice the skills. I left the group responsibilities up to my colleagues, never spoke up nor asked questions during rounds (which at that time were held around the bedside). As a result my fourth year was almost a complete waste of time, other than pulling me into a depressive state and filling me with self doubt. Needless to say, by the time I got to fifth year my grades were average and I was an uninspired aimless student.

I happened upon a small book by the British physician MH Pappworth called ?A Primer of Medicine (1).? His introductory chapters on ?Ethical Precepts,? ?Learning and Teaching Medicine,? and ?The Art and Science of Diagnosis and History Taking? were pure music that inspired my soul. They were all I needed to spark my career in earnest. I carried, read and reread the book like a bible.

Just a few quotes in the book made the difference. Pappworth stated that ?probably in no field of human knowledge is a true start more important and a false one more disastrous than in clinical medicine.? It was a frightening statement for me since I felt I had gotten off to a poor start, and I did not like the sound of ?disastrous? and ?career? on the same thought wave.

Many other inspiring quotes were relayed in Pappworth, including:

?Knowledge is an essential prerequisite to performance? (Rabbi J.H Hertz),

?Sapere vedere? ? learn to see things (da Vinci),

?Medicine is learned at the bedside and not in the classroom,? and

?To study medicine without books is to sail an unchartered sea, whilst to study medicine only from books is not to go to sea at all.?(Sir William Osler).

Maimonides, the great 12th century Spanish rabbi and physician, suggested that a good student should ask questions when something is not understood. One should not be embarrassed to ask questions; if one does not ask one will never learn. Paracelsus imbued a spirit of loving the patient: ?Then to love the sick, each and all of them, more than if my own body were at stake.?

These quotes fired and inspired me, and changed my whole approach as I planned my journey for a career in medicine. I formulated ways that fostered learning and understanding rather than learning rote methods that in the past helped me pass examinations. For example, I realized that symptoms arose from irritation or malfunction of an organ or system. So while taking a cardiac history, I came to categorize questions that would suggest irritation, including chest pain and palpitations, and questions of malfunction, including dyspnea and leg swelling. Using principles while taking a history rather than relying on pure memorization empowered me. Mnemonics did not hack it ? thoughtful questioning did!

Methods of examining the patient required learning a technique that made inherent sense. Rather than first examining the cardiovascular system (heart in the chest) and then the nervous system (head and neck and limbs), and then the respiratory system (chest again for the lungs), it made better sense to examine both the heart and the chest while examining the anterior chest. It seems fairly logical as it is explained now, but this was not clear from my teachers or books of the time.

So I developed a method for myself that made spatial sense. I started by making sure I made eye contact and then holding the patient?s hand for a brief moment (a psychologically advantageous and human gesture). I quickly turned to professional business by starting the examination of the hand. First the nails and then the palm, to the radial pulse, up to the antecubital fossa to the axilla, up the neck, then to the cranial nerves and then down to the chest. It was easier and more logical for me to follow a spatial pattern up the arm and neck to the head and then down to the chest abdomen pelvic and limbs, rather than examine the patient using a systems approach. I realized that the professional examination had to be smooth, quick, efficient, yet kind, warm, and thoughtful.

Once I refined this method, I would run through the examination in my head as I went back and forth to medical school, before I went to bed, and while in the shower, so that it eventually became a mindless maneuver ? just like a flamenco dance sequence. Whether executing a dance step, a tennis stroke, playing the piano, examining the patient or performing neurosurgery, I learned that a method had to be developed that allowed smooth execution of the skill. This required thought, preparation and then practice of the skill until the pattern was ingrained in the cerebellum, which then allowed a mindless execution of the movement. This approach is one that I believe is necessary in every single skill that one wants to master. It later became a technique which I promoted with colleagues as a method of learning the skills in learning to read an X-ray, called ?Notes Scales and Music.? The ?notes? were the anatomical parts involved, the ?scales? represented the method or pattern employed to examine the film, and the ?music? represented examples of real life situations. The sequential steps in learning and pursuing excellence have to be taken in order. Anatomy first, then the method of looking (?practice practice practice?), and then, and only then, comes the music which by its nature the most pleasurable. Our natural instinct of expedience always inappropriately pushes us to the music. In the pursuit of excellence we have to face and finish the grunt work first. The music will be better appreciated, remembered, and executed if the correct order of things is followed.

In the pursuit of excellence therefore, one has to:

identify the skill required

acquire a teacher,

identify the parts that make up the skill,

create a method of putting the parts together,

practice the method, and

apply the skill with ?hands on? to the real life situation.

In medicine the elemental skills include the acquisition of knowledge and judgment, acquisition of technical skills, and learning the expression of compassion

We become valuable both for making decisions based on our knowledge and experience (an intellectual skill), and also for our technique driven skills. We become satisfied when we do these well and become fulfilled when true compassion is present.

The method of approaching these two skills is very different, and as physicians we have to master both. Some of us are better equipped with intellectual skills and are more valuable as internists, while others are better at technical skills and are therefore more valuable in the surgical disciplines.

A concept called the pursuit of ?oneness? also helped me understand the pursuit of excellence. The mastery of any skill that is made of many parts requires practice so that the skill eventually is executed as one movement.

In the second after a chest X-ray appeared on the reading board, Dr Jerry Balikian a teacher of mine and a skilled veteran chest radiologist was able to pronounce, ?Normal? next!? or ?Lung nodule ? follow up.? He seemingly was ?at one? with the chest X-ray and was able to integrate the many aspects and complexities required to read the chest x-ray almost as quickly as he set his eyes on the image ? in mere seconds. In the clinical realm this gift is called ?geshtalt.? The skilled clinician after years of thoughtful practice has acquired an innate sense and is able to put together a geshtalt the moment the patient walks through the door of the office. Perhaps it is the way the patient looks, walks, talks or smiles.

The perfect shot by Tiger Woods, the perfect execution of a piano concerto by Rubinstein, or the perfect execution of a sculpture by Rodin has a wholeness or oneness about it. It takes years of daily practice and dedication to make it look so easy, but once accomplished it is a pure joy to witness the perfection.

Medicine is going to be your profession. You need to do it for the rest of your life, yet you have time to master it. Approach it with the zeal and dedication of a Tiger Woods, Rubinstein or Rodin.

Compassion and Caring

Some are born with it ? most work toward it.

In the rush of the day, and in the changing environment and culture of our profession, we have to be continually reminded that compassion is our highest aspiration and for most brings the greatest satisfaction. ?You give, you get,? I tell my children. If you give true compassion and care you will receive true appreciation.

At the end of the day, the perfectly executed operation, or a diagnosis made by geshtalt may satisfy the ego which is necessary for our self worth, but in the absence of kindness and compassion it falls empty. True concern for our patients takes minimal additional effort, and does not take innumerable hours of dedication, but in the end goes a much longer way. All the compassion in the world, on the other hand, will not go anywhere if it is not delivered with excellence in the skills required by the profession.

The sense of kindness and compassion should start at home with those closest to us, because if it cannot happen at home it will not happen with truth and honesty at work.

Delivering compassion requires a disciplined mindset and daily reminders of how to provide emotional care. It may be that you start with a greeting that includes a kind smile, followed by a genuine need to listen, and an attempt to see and treat the whole patient.

Inspirations can be found in every generation of greats, starting with Hippocrates through Einstein and the Dalai Lama, who all reflect on this important aspect of humanity.

Hippocrates of Cos (460-377BC), the father of medicine, inspired the famous oath repeated around the world through millennia by graduating medical students: ?With purity and with holiness I will pass my life and practice my art.?

Maimonides was a rabbi, philosopher, and physician who practiced in Spain and Egypt (1135-1204). His words have also been incorporated into oaths for graduating doctors: ?May I see in the afflicted and the suffering only a fellow human being in need.?

The Swiss physician Paracelsus (1493-1541) inspires with the words ?This is my vow. To perfect my medical art and never to swerve from it as long as God grants me my office, and to oppose all false medicine and teachings. Then to love the sick, each and all of them, more than if my own body were at stake.?

You must feel and act as a gentleman? said Sir Benjamin Brodie, a British surgeon (1783-1862). ?It is he who sympathizes with others, and is careful not to hurt the feelings even on trifling occasions.?

Dr Pappworth describes thirteen principles of medical ethics. One of these deals with compassion and care. ?I will always deal with my patients with sympathy and loving care, regardless of their race, colour, nationality, religion, party politics, or social status.?

In the world at large, outside of medicine, others have focused on compassion as well, and have set examples for us to follow.

The great physicist Albert Einstein saw our responsibility in the scheme of the universe.

?A human being is a part of the whole called by us universe, a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feeling as something separated from the rest, a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.?(*Firsing)

The Dalai Lama said that ?If you want others to be happy, practice compassion. If you want to be happy, practice compassion.?(*REF)

Daniel Goleman is an American psychologist who wrote a book called Emotional Intelligence in 1995. He focused attention on the path to empathy. ?The act of compassion begins with full attention, just as rapport does. You have to really see the person. If you see the person, then naturally, empathy arises. If you tune into the other person, you feel with them. If empathy arises, and if that person is in dire need, then empathic concern can come. You want to help them, and then that begins a compassionate act. So I?d say that compassion begins with attention.(Goleman)?

Compassion has to be on our mind from time we start our day. Develop a habit that reminds yourself of this duty until it becomes part of you. Perhaps as we take the first sip of coffee or tea, or first morsel of food in our mouths, we should appreciate the simple things of life, taste the food, and in that moment of Nirvana, think of kindness and caring.

References

1)Pappworth, MH. A Primer of Medicine, 3rd ed. Butterworth & Co., London, 1971.

2) Michael H. Ross, Edward J. Reith, Lynn J. Romrell, Histology: A Text and Atlas, Second Edition, Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore MD, 1989.

3) Firsing, Scott Disturbing Times: The State of the Planet and Its Possible Future. 30 Degrees South Publishers , September 2008.

4) Goleman Daniel Emotional Intelligence Bantam Books New York 1995